photo source

The farmland acquisition mania is spreading like wildfire. People who don't know one thing about the business of farming are idealizing it as a safe haven during this time of economic uncertainty. They are looking for something that is real. They are tired of being on the receiving end of "punish the saver" policies.

Farming is and always has been risky. It carries risks of illiquidity, weather, commodity price volatility, and most importantly, the risk of political pen-strokes. Even so, just as Deere & Co. is reporting that 2010 and 2011 are to be their most profitable years ever, the large scale farm operator is euphoric with currently high returns and is also enthusiastic to acquire additional land.

Articles have been appearing often lately expressing concern about farmland price appreciation. Recent examples are from the DesMoines Register "Why Farmland is Skyrocketing", from the WSJ "The Farm Belt Boom - Land prices are soaring. Is this another Fed asset bubble?", and from the Omaha World Herald "Land's Back in the Picture".

Our nation's own Chairwoman of the FDIC, Sheila Bair, expressed her concern about the possibility of a bubble in farmland prices in October 2010. In November, Kansas City Federal Reserve Chairman Thomas Hoenig told an Omaha agriculture bankers' conference, "I also see the value of farmland (going up) and people looking to deploy lots of liquidity, looking for opportunities. I see that prices are rising above what the productive capacity of that land can support."

I was an early voice expressing concern about farmland prices, much to the disapproval of the numerous Jim Rogers and Marc Faber groupies. My caution was based primarily upon my expectation of deflationary forces driving down commodity prices as a result of weak consumers globally along with the expectation of less generous farm price supports due to balance sheet budget constraints.

My macroeconomic expectation of deflation, though it was not wrong, did not play out like I expected due to political intervention leaning towards unlimited bailouts, and stimulus measures rather than austerity. Or, perhaps it has yet to play out. Even so, many of the Ag bulls from eighteen months ago were bullish for the wrong reasons such as we are going to have massive inflation, "the world is running out of grain", and over anticipating that the developing nations will be eating more meat as we've learned recently that China has already slowed its growth in meat consumption.

It All Comes Down to Policy

This recent economic disaster was a failure of politics at its root level. Our farmland price increases are a result of current politically driven Ag policies plus a lack of faith in our currency. We've got farmers making excellent profits off corn and ethanol price supports. Ditto soybeans, cotton, and other farm products. We've got desperate wealthy investors looking for safe havens for their cash and retirement monies who are distrustful of paper and electronic assets and fearful of inflation. We've got an economy barely growing and unable to employ its labor force.

We now know that the soon-to-pass

Where would land prices in Iowa be without corn ethanol taxpayer support plus corn subsidies? Iowa is using over 50% of its corn, or 2.2 billion bushels, to produce one-third of this nation's ethanol offering a corn price support of approximately $2 per bushel. In times of austerity, will policy continue to support overproduction? Will policy-makers listen to the concern and desire of its citizens to support the smaller family farm operation which could reward goals other than monoculture commodity production?

There are recent rumblings of rising cash rents which in turn support land price increases. Surveys have shown that 40% of acreage is now cash rented in the corn belt region. As I reported two months ago, Gary Schnitkey from the University of Illinois reports that farm rents are not keeping up with underlying land values as shown in his graph below, a cause for concern.

If farm profits fall farmland prices will go down

Let's go over some reasons profits could fall.

- Deflation and deleveraging may persist, causing commodities and farmland prices to fall globally. This continues to be my number one concern in my outlook for a potential fall in farmland prices. The global consumer must be able to support price levels irregardless of input costs. A weak global consumer combined with farm program austerity cut-backs in a deflationary era would cause large commodity surpluses and resulting low prices. Surprise: Ag commodity prices are not determined by the number of people on the planet.

- Policy might end the corn, biodiesel, and biofuel subsidy programs.

- Land leveraging is on the upswing. If interest rates increase the leveraged owner is in a vulnerable business position.

- Poor production might be caused by weather volatility, droughts, floods, storms, lack of fertilizer, weed or other pest problems.

- Oil prices will continue to go up driving input costs higher for agriculture. There is increased global competition for oil and diesel fuel.

- Higher farmland property (and other) taxes may result to help fill regional and federal budget shortfalls.

- Lower farmland rents could result from any combination of factors on this list.

- Lower commodity prices may result from the European debt crisis precipitating a continued economic crisis with global contagion.

- A stronger dollar may result from an ongoing European debt crisis.

- Expected Ag commodity price volatility may spook investors.

- Increased Ag commodity production and improved storage and transportation infrastructure in South America, Africa, the Ukraine, and Asia along with GM advancements could result in Ag commodity surpluses in this coming decade.

- Regulation of commodities speculation (now being considered) could drop prices.

- Regulation restricting the use of pesticides, herbicides, the types of seeds, how much irrigation is available, and any number of other factors could hurt farm profits.

- The aging farmer demographics could bring much more land onto the market in the not too distant future.

So What Defines a Bubble?

Farmland prices have doubled in a decade. In the dot-com bubble, the NASDAQ went from 800 in 1994 to 5000 in 2000, or 625%, doubling its value in the final year. In the housing bubble we saw prices increase, on average, by 240% in nine years. Gold has gone up 460% in the past eleven years.

Most recently, farmland prices have increased by about 20% in the past three months in Iowa, according to the DesMoines Register.* That was on top of a 13% increase earlier this year. But, you say farmland is not leveraged now as it was in the 1980's farm crisis. While this is true with 75% of Iowa farmland paid for today and a 35% down payment requirement, this would not necessarily prevent a tech-type bubble if there were an unusually high number of willing cash buyers available. Currently there are many more buyers desiring farmland than there are sellers. A bubble in farmland prices could also simply be caused by prices appreciating rapidly followed by farm profits diminishing rapidly, for whatever reason.

Most recently, farmland prices have increased by about 20% in the past three months in Iowa, according to the DesMoines Register.* That was on top of a 13% increase earlier this year. But, you say farmland is not leveraged now as it was in the 1980's farm crisis. While this is true with 75% of Iowa farmland paid for today and a 35% down payment requirement, this would not necessarily prevent a tech-type bubble if there were an unusually high number of willing cash buyers available. Currently there are many more buyers desiring farmland than there are sellers. A bubble in farmland prices could also simply be caused by prices appreciating rapidly followed by farm profits diminishing rapidly, for whatever reason.

To use our most recent historical example, let's review how our last farmland bubble happened twenty-eight years ago.

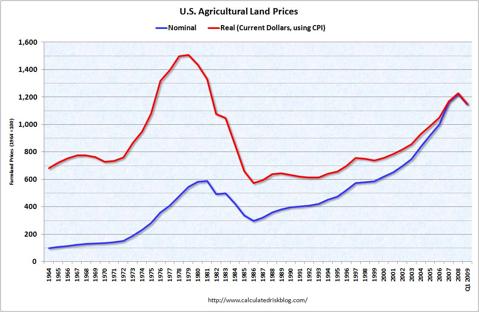

The agricultural lending crisis of the early 1980s had its roots in the agricultural export boom of the 1970s. U.S. agricultural exports rose over 500 percent from 1972 to 1981 (from $8.24 to $43.78 billion), which in turn led to a dramatic rise in commodity prices and farm incomes over the time period. Net farm income peaked at over $27 billion in 1979, a rise of 41 percent over the decade. Iowa, a bellwether state in terms of farm prices in the corn belt, saw the average price of an acre more than quadruple from 1970 to its peak in 1982, only to lose nearly two-thirds of its value over the next five years. Over the same time period, the average price of farmland nationally also rose rapidly, increasing more than 350 percent by 1982, before falling by more than a third by 1987.

The increase in farm land values was accompanied by an increase in agricultural debt loads, as many farmers borrowed to acquire additional acreage. Because they lacked the needed cash and because they expected increased cash flows, many farmers used variable-rate notes to purchase real estate. Farm loan underwriting standards eased, and a speculative lending boom ensued.

Lenders began to rely less heavily on the ability of borrowers to service their debt from operating cash flows and more on the continued appreciation of the underlying collateral—the farm land—for repayment. But when demand for farm goods began to fall, farm real estate prices also fell precipitously. As farms’ cash flows decreased and the variable-rate notes used to purchase farm real estate reset, many farmers saw their interest rates increase and found that they could not make payments and were underwater on their mortgages.

Farmland values peaked in 1981 in the Midwest, where the land-price appreciation had been the greatest, and declined by as much as 49 percent over the next few years before bottoming out in 1987. Farm-sector debt quadrupled from the early 1970s through the mid-1980s. Debt declined by one-third from 1984 through 1987, but much of this reduction reflected the liquidation of farms. (source: Cleveland Fed)

The Federal Reserve Board of Minneapolis defines a bubble for us:

In a given equilibrium, an asset’s price has a bubble if the price exceeds the asset’s buy-and-hold-forever value (which is, again, the price that a buyer would be willing to pay if he were required to never resell it). Over short periods of time, an asset’s price could grow more rapidly than the economy–but this trend cannot continue forever. The key is that (the owner) anticipates (with reasonable confidence) that there will be a buyer willing to buy the bubbly asset at that critical point in the future. In this sense, a bubble is a form of collective trust.

Judging by my comparisons of our recent farmland price appreciation to other recent bubbles it would seem possible that farmland prices could still have a run-up given an economy no worse than we have today and continued high commodity prices. Gold and farmland are two assets referred to as tangible and the farmland price appreciation is far below that of gold's 460%.

As history tells us above, what can drive a farmland bubble is the mania surrounding high commodity prices. This year we've had a more than 50% increase in corn and 30% in soy prices. From the DesMoines Register's recent article about farming during the Great Depression came this statement, "History teaches that both the Great Depression of the 1930s and the farm crisis of the 1980s were preceded by a similar boom in land and commodity prices in 1918-20 and 1972-75 that Iowa has had this year." The article also issues a wise warning of concern about the lack of diversity from Iowa farm production today. Improved today, however, is an opened world market with China buying 60% of U.S. soybeans, for example. Iowa restricts land ownership from outside of the state, shutting out many would-be buyers. Other states, including Illinois, are less restrictive.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There's nothing like comparing what you can buy with the same amount of money to help put some perspective on an asset's value. Next, let's compare some assets and look at each one's annual return.

Let's Make Some Comparisons

Currently, two million dollars would buy you....

- 500 acres of dryland cropland in Nebraska

- 250 acres of dryland cropland in NW Iowa renting for $300/acre, or $75,000/year

- a 5,000 square foot home in Denver, CO (renting for $5,200/month or $62,400/year)

- a 1-year UST bill earning $5,600

- a 10-year UST note @3.29% earning $65,800

- 42.6 kilo bars of gold bullion

- 113,960 shares of Duke Energy yielding 5.9% or $118,000/year

- 22,612 barrels of crude oil

- 340,136 bushels of corn

- a 67-unit hotel on 10 acres in Rocklin, California.

- a new or existing McDonalds franchise

Investing in Foreign Farmland

As I stated in my recent post about this subject, I consider investing in land across borders to be very high risk. Our world faces too many insecurities and global risks to assume that new or old foreign farmland ownership contracts would be honored during times of national stress or leadership upheavals. Instead, foreign owned farmland could quickly become nationalized making such investments worthless overnight. "The only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history."

Why might farmland prices continue to appreciate?

Finally, I will present points in defense of farmland price appreciation.

- Inflation will take off making farmland a good investment.

- Politics will continue to support generous farm subsidies.

- Currently the big farms are getting bigger and that trend will no doubt continue in the foreseeable future further driving land prices upwards.

- Corporate buyers for investors are offering buyouts in exchange for land lease agreements, helping to drive up land prices in some places.

- A lack of alternative safe investments will continue to drive investment in farmland.

- Wealthy investors are making cash land purchases.

- A weaker dollar supports Ag commodity exports though it raises oil and fertilizer input costs.

- Rights for mining, wind generator rents, and water may be responsible for some land appreciation. (Currently a wind generator sitting on 1 acre of land pays $5000/year.)

- Increased demand by foreign investors.

- If the economy continues to recover, the demand for recreational land will return.

- It is impossible to know a bubble's top and it is possible that appreciation in farmland prices could continue for a very long time.

- If global economic health is strong, Ag commodity purchases will continue to grow.

- If climate change induced weather patterns prove kinder to the Midwestern region than to other farm-belt regions of the globe, U.S. corn belt land prices could be driven up.

On the Big Getting Bigger

The trend of farms getting larger is continuing with momentum. Large farms have less risk due to economies of scale. In 2009, the top 10 percent of recipients were paid 61 percent of all USDA subsidies and six percent of farmers owned 40% of the farmland. In order to generate investor profits, larger tracts of land are necessary. The goal is to drive down costs through efficiencies of scale and methods. Translated, that means huge unobstructed fields where mega-sized equipment covers vast areas driven by GPS systems so not even several inches of overlap is wasted in input costs. The equipment is so expensive that only the largest of farms can use it profitably.

The most efficient seed, chemical, and fertilizer inputs with the fewest annoyances such as weeds, fences, trees, or wet areas are what is striven for with an added bonus of requiring minimal human labor. According to a report out of Purdue, it is expected that in a decade from now 5-6% of the farmers will operate 50% of the acreage. No doubt government policy will continue to support these largest operations as they will be the consumers of big agri-business products and the source of commodity exports for the U.S.

The Voice of the Farmer

From a variety of sources both first and second-hand I am getting the message that the local farmer or producer thinks current land prices are too high and can't be sustained.

"I am trying to buy some farmland in Central Illinois where it is prime, and it is consistently bringing in 8-9k per acre. Holy Cow, over 13K an acre? With 200 bushel corn at 5.50 a bushel will gross you 1100 an acre. With 600-700 per acre of inputs, I can't see how this would ever pay off.

and another....

Every measurable increase in the marketable price of commodities gets immediately bid into the inputs (seed, equipment, herbicides, pesticides, etc.) including land and rents, with limited or no short term negative corrections."

But this farmer voice is more bullish, "$8,000/acre is undervalued given you can make a $500/acre profit growing corn."

Concluding Questions

So are farmland prices a bubble because underlying fundamentals cannot support a long term upward trend given a deflationary environment and a national debt level requiring a less supportive government farm program OR can farmland prices keep going up driven by large industrial farm owners and wealthy investors with trillions of dollars of investment capital looking for a safe haven? What is the future of Ag policy? Will Ag commodity prices stay high a few more years driving land prices into true bubble territory? Could they collapse? Will demand continue to exceed supply of farmland?

And, finally....What will an average acre of farmland in Iowa cost ten years from now? Sorry. I can't answer that. My crystal ball is looking very cloudy today. But hand me that deck of tarot cards and I'll tell you....

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

*The new Iowa 2010 price report out by Duffy (released today) states that the average value of an acre of farmland in Iowa increased 15.9% in 2010.

Note that this is the seventh and last of my November farmland report series, the previous ones are linked below.

November 2010 Reports to date: