Triticum

"There is a wheat crop harvested somewhere in the world every month of the year."

Wheat is well adapted to harsh environments and is mostly grown on wind-swept areas too dry and too cold for rice and corn. It supplies about 20 percent of the food calories for the world’s people and is a national staple in many countries. In Eastern Europe and Russia, over 30 percent of the calories consumed are from wheat. About one-third of the world's people depend on wheat for their nourishment.

Unlike rice, wheat production is more widespread globally though China's share is almost one-sixth of the world. Wheat holds an important food-security role in a growing world population. The per capita consumption of wheat in the United States exceeds that of any other single food staple.

On average, in the U.S., one acre yields 37.1 bushels of wheat. One bushel weighs 60 pounds and contains approximately one million individual kernels.

60 pounds of wheat produces...

- 60 pounds of whole wheat flour

- 42 pounds of white flour

- 42 commercial loaves of white bread

- 42 pounds of pasta

- 45 boxes of wheat flake cereal

- 210 servings of spaghetti

In 2004 the world leaders in wheat production were:

- China (91.3 million tons)

- India (72 million tons)

- United States (58.8 million tons)

- Russia (42.2 million tons)

- France (39 million tons)

- Australia (22.5 million tons)

Top Wheat Exporters:

- U.S.

- Canada

- Australia

- European Union

- Argentina

Top Wheat Importers:

- China

- Belarus

- Brazil

- Thailand

- Indonesia

- Mexico

- There are two general types of wheat, Winter and Spring, reflecting the time of year the seed is planted.

- Winter wheat is 70-80% of U.S. production

- There are several hundred varieties of wheat produced in the United States, all of which fall into one of six recognized classes.

- In the United States the wheat belt covers the Ohio Valley, the prairie states, and Eastern Oregon and Washington. Kansas leads the states in production.

- Large-scale mechanized farming and continued planting of wheat without regard to crop rotation have exhausted the soil of large areas.

- High-yield wheat, one of the grains resulting from the Green Revolution, requires optimal growth conditions, e.g., adequate irrigation and high concentrations of fertilizer.

In 2007 there was a dramatic rise in the price of wheat due to freezes and flooding in the northern hemisphere and a drought in Australia. Wheat futures in September, 2007 for December and March delivery had risen above $9.00 a bushel, prices never seen before. There were complaints in Italy about the high price of pasta.

This followed a wider trend of escalating food prices around the globe, driven in part by climatic conditions such as drought in Australia, the diversion of arable land to other uses (such as producing government-subsidised bio-oil crops), and later by some food-producing nations placing bans or restrictions on exports in order to satisfy their own consumers.

Farmers around the world responded to the high prices that resulted from the tight global stocks-to-use situation in 2007/08, and the resulting additional foreign supplies have steadily reduced the demand for relatively higher priced U.S. wheat.

Most interestingly, in a 2009 FAO report by David Dawe, he lays out some of the complicating factors of obtaining reliable global grain stock data. He goes on to explain how China's huge draw down of stocks during this past decade skewed the data to suggest that stock to use ratios were approaching dangerous levels, when in fact, by removing the China statistics, the data appeared quite normal.

Other drivers affecting wheat prices include the movement to bio fuels (in 2008, a third of corn crops in the US are expected to be devoted to ethanol production) and rising incomes in developing countries, which is causing a shift in eating patterns from predominantly rice to more meat based diets (a rise in meat production equals a rise in grain consumption - seven kilograms of grain is required to produce one kilogram of beef.)

Challenges

In many countries, if the price a farmer receives is too low to cover the cost of production it may be subsidized through a government agreement. Some governments subsidize grain transportation. In the United States, the subsidization is called a deficiency payment. An average cost of production is calculated and the difference between market price and the cost of production is the amount that the government will subsidize, within pre-set limits.

The U.S. wheat sector is facing long-term challenges as productivity gains and returns for competing field crops outpace those for wheat. During the next decade, wheat-yield improvements are expected to continue lagging behind those for competing row crops, primarily corn and soybeans. Low relative wheat prices are due, in large part, to continued foreign competition, from both traditional wheat-exporting countries and some newcomers.

Furthermore, domestic food use, while growing, no longer provides the dynamic market growth experienced in the 1970s through the mid-1990s. Consequently, farmers will focus on other crops, such as corn and soybeans, because of low returns on wheat. Over the next 10 years, the U.S. wheat planted area is projected to fall from the recent high in 2008/09.

Various trade issues are a challenge to some of our faithful buyers at a time of abundant supply. Partly as a result, U.S. wheat's global export share has fallen to 22 percent from 30 percent in the last year. The strong dollar continues to hurt U.S. grain exports.

Farmers face many challenges like weather, insects and fungus that may diminish a once profitable wheat crop. Developing and planting wheat varieties that resist diseases and insects is essential for a secure food supply, human health, and reducing the use of chemical controls. For example, fungal diseases like Karnal bunt, leaf rust, or smut will ruin entire wheat crops.

Current Supplies

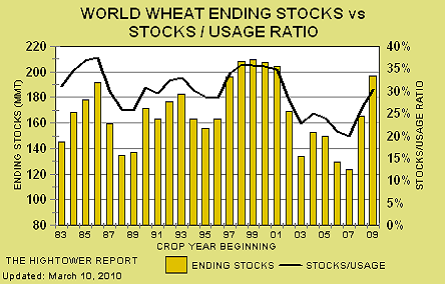

Except for the 5-year period of 1997-2001 that had ending stocks at around 200 million tons and with corresponding low wheat prices, wheat stocks have never reached the current projected level. While global consumption has grown, stocks are still expected to reach 30.0 percent of use for the 2009/10 marketing year, up from 18 percent just 2 years ago. Large supplies should put additional pressure on wheat prices and intensify export competition.Russian ending stocks are the highest level in 16 years although storage capacities and structure in Russia are far from being either sufficient or efficient. Exports from Ukraine and Russia are projected to continue gaining market share, more than offsetting a slight decline in the share held by Kazakhstan. However, because of the region's highly variable weather and yields, year-to-year volatility in production and trade can be expected.

In March, US 2009/10 ending wheat stocks were raised to 1.001 billion bushels, their highest level in more than 20 years. Remember that, remarkably, ending stocks stood at just 306 million bushels only 2 years ago. World wheat ending stocks bumped up as well to 196.77 million tones. Global stocks to usage surged by over 50% of 2007/08 levels.

The current but ever changing dynamics include increased production plus a currency export-boost in the European Union and an expectation of export-subsidies to support hurting farmers there, while production is significantly reduced in North America as price incentives have disappeared. The FAO expects global production to be well above the five-year average for this year, however.